For Millennia humans have been drawn to rivers. Although today’s river visitors look different than those of past history, their motive is very similar. People still flock in huge numbers to moving bodies of water. These rivers provide a place to gather, travel, and recreate. Rivers often appear tranquil and slow but carry with them a deadly force. They have the ability to deliver a relaxing tube ride, or a thrilling whitewater adventure. A basic understanding of Swiftwater Awareness is helpful to would-be river enthusiasts.

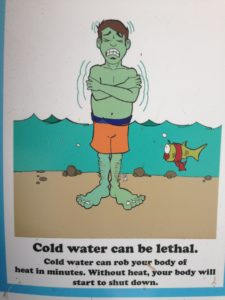

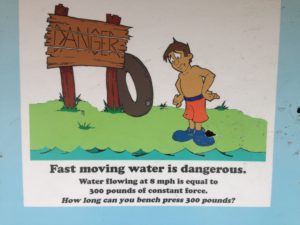

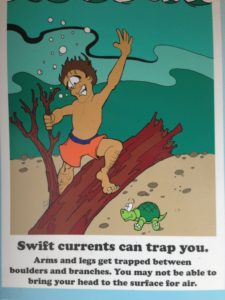

Several characteristics of moving water can disrupt the tranquil time spent at or in a river, and quickly change a relaxed scene into an urgent one. Across the United States and abroad, governing bodies and regulatory agencies are trying to increase the general public’s awareness of swiftwater hazards and how to prevent injury and exposure. Have a look at California’s take on public notifications and posting of swiftwater awareness. This cartoon signs are posted at the entry to a few of the river access sites along the Yuba River.

Providing an equivalent comparison to the force of water attempts to give visitors something they can relate to. Moving water is deceptively strong and can easily overpower even strong swimmers. Don’t underestimate moving water and always have the proper gear before you go.

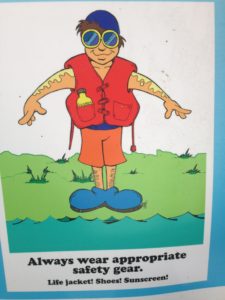

The Boy scout motto has significant merit here: “Always be prepared.” Know the river environment and make sure that the proper gear is used. 95% of all drownings in swiftwater the victim wasn’t wearing a life jacket or Personal Floatation Device. In addition to the PFD, shoes, hat, and sun protection are crucial.

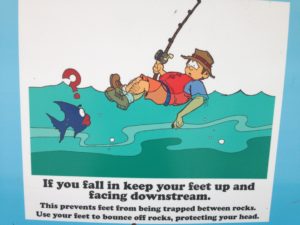

Foot Entrapment is deadly. Keep your feet up! Think about the position you are in and were your most likely exit from the river is. The most important thing is to stay calm and focus on your own survival and self-rescue.

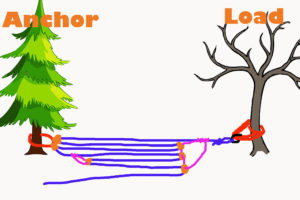

This picture demonstrates how subsurface hazards can be deadly. There’s no telling what lies beneath the surface and the reality is that there are unseen hazards that can entrap a person. Rembember the current never lets up, and if you are stuck then you’re stuck. Don’t put your feet down if the current is pushing you downstream.

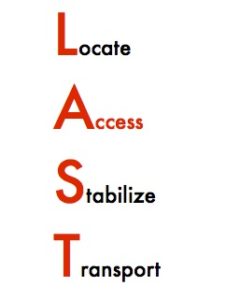

Promoting swiftwater awareness is an important step to increase public safety in and around moving waterways. Flyers, signs, written hazard warnings, whatever for the message takes it is the responsibility of the visitor to acknowledge the risks and stay safe. We work wit agencies arcross the United States that respond to calls when people fail to comprehend the gravity of the swiftwater situation they have put themselves in.